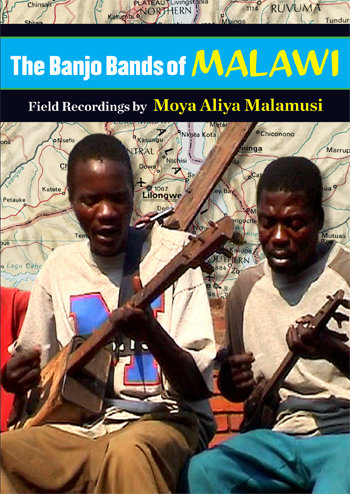

The Banjo Bands of Malawi

Banjos have been used in southern Africa for a long time as musical tools that can be made locally, for solo performance or playing in a group. Factory-manufactured American banjos were introduced in the 1920s and 30s. At the end of World War II they had become prominent dance music instruments throughout the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953-1963). But from the mid 1960s such instruments, even guitar strings, disappeared from shops in the newly independent countries, Malawi and Zambia. Adolescents began to experiment on their own.

It was from the late 1970s that young boys with homemade banjos were increasingly seen at street corners, on country roads and around towns. They began to not only to construct banjos but also guitars, percussive devices as well as a huge bass banjo/guitar, usually with a single string, played with stick or a bottle as a slider.

This is a vibrant culture, neglected by the local mass media that go for the established dance music played with electric guitars, keyboard and synthesizers. From the 1990s until recently, however, the music played by itinerant adolescents was the most varied and most frequently encountered small group musical activity across Malawi and parts of Zambia. Their audiences are found at market places, mini-bus stations, various other points of gathering and also in or near their home villages at dance parties. Their repertoire is a creative mix of personal compositions (music and text) in the style of current media transmitted music, from chimurenga to reggae etc., but usually much more complex than the models which are emulated.

Many people are not aware of the intense experimental spirit that pushes these boys. They continually invent or discover new terrain in acoustics and performance technique. This collection presents a wide variety of audio-visual field recordings filmed by renowned Malawian cultural anthropologist Moya A. Malamusi.

Also included on the DVD is a PDF booklet with biographical material about the musicians as well as historical information and a discussion of the banjo in Malawian culture.

Running Time: 78 minutes

Review: The 'Field Recordings' tag on this DVD immediately brings me to thoughts of Alan Lomax and the incredible recordings he made of artists he found in the depths of Mississippi and across the US (as well as the rest of the world after the US Library of Congress withdrew his funding). These are recordings of itinerant musicians in Malawi in Southern Africa and, on largely homemade or locally built instruments, the music is completely natural, fresh and joyful.

The banjo was a common instrument in the days of the European colonization of Southern Africa but later became increasingly difficult to find so the musicians of Malawi and Zimbabwe started to make their own. If you consider the instruments made by the legendary Super Chicken in Clarksdale Mississippi, one stringed basses and unique guitars using Cigar boxes for a body along with oil cans and broom handle necks, these are in the same family. Personally I would put the instruments closer to a Ukulele than a Banjo but there is a definite familial link so if they want to call them banJos then that fits as well as any other.

Musically the instruments are used almost as percussion instruments to back up the chants of the musicians with very little soloing although the individual talents of the musicians is undoubted. One instrument that appears often is a one string lap played bass banjo which is played with a slide action that actually mimics the sound of a talking drum when plated slide style. The voices are all individual and the handmade nature of the instruments means that there is a symbiosis between the voices and the music. This is music for the enjoyment of the musicians as well as the crowd and almost all these recording are in a street situation so one can imagine the dancing happening out of shot. Great music and captured with real understanding of the music and the players. – Andy Snipper/Blues Matters

Review: You've heard "Willie And The Poor Boys" by Creedence, but picture in newly independent African countries that commercially manufactured instruments, or even guitar strings, would no longer be available. The Creedence song is an artistic description of Will Shade and the Memphis Jug Band. Now, with this new DVD we have field recorded videos of what passes for garage bands in a country where hardly anyone owns a car, so there are no garages! The teenagers have to make their own banjos out of gallon (or two liter) cooking oil tins, or whatever else they can find, the drummers make do with arrays of pots and pans and tin cans plus tambourines made of wires strung with bottle caps, and the bass players make their own one string instruments (same thing as a Diddley bow), playing them with sticks or metal bars. These kids ply their trade in the town squares, and the result for me is not just fascinating, but even thrilling! Several different bands in different towns are featured, and the music is described as being inspired by contemporary commercial dance music they hear on the radio, but original and more complex. It surprised me that in the first several clips the only dancing I saw was a couple of small children, but that bit was precious. Later on one band had a bunch of folks rockin', and I was surprised to see some of them doing something that resembled the Twist a little bit! Anyhow, this 78 minutes is very cool! Now I want to see sound films of the Jolly Boys playing on Errol Flynn's yacht or their favorite local pub from the 1950s! I don't know if such a thing exists, but I love that West Africa meets the New world stuff in most all its incarnations. This DVD is pure Malawi, and I love it! – Marc Bristol/Blue Suede News

Review: Valuable travel tip: Don't run out of gasoline in Malawi. Because you'll be forever stranded, unable to lug back a spare gallon. Evidently, the southeast African nation's supply of squared-off metal cans has been scavenged in the name of grooving - more specifically, to concoct the world's most surreal banjos. Shockingly crude, heroically ingenious, and explosively loud, these primal instruments get handmade by impaling one of those five-liter cans with a wooden handle strung with found wire or fishing line. Then they're mercilessly drubbed by their DIY virtuosos. Monster one-string diddley-bow basses and scrap-pile percussion rigs typically ride shotgun.

For 78 drop-jawed minutes, you and expert tracker Moya Malamusi go on safari for the greatest junkyard orchestras you'll ever hear this side of Lilongwe. Red-dirt villages hide jackpot after startling jackpot. There, as recently as 2010, amid chicken free-for-alls, tumbledown rubble, and spontaneous fits of dancing, is where the Makambale Brothers Band hangs, conspicuous rockers commanding a bandstand of packed clay. And where the peewee Tiyese Nawo Band, darling pride of Masakamila, dispenses smiles with every buzz and bang. Unlike the others, Evans Manyozo is a one-can band, even managing to plunk out a solo despite holding down the fort all by himself. Still, there's no denying that the show gets stolen when 13-year-old Sila Chaphadzuka whips his paint-can drums like a pint-sized Elvin Jones while chirping out lines in Chichewa. Never in a million years, though, would you guess such frenetic, jangly joy could be so blue, its euphoric rhythms and soaring sky-high vocals actually camouflaging gloom ratted out in translations like "When Going to the Grave" and the far subtler "Joyce in the Bar, No!" You definitely needn't be in love with the banjo (or even its crazy cousin) to relish this rare chance to gawk at the brilliant spirit of music-making in its rawest, whatever-it-takes form. You just have to be willing to be absolutely astounded. – Dennis Rozanski/Blues Rag